The great thing about a career retrospective is that it can trace the evolution of an artist over time, shining a light on early or minor works. The great thing about a career retrospective at the Guggenheim is that the building forces the viewer to move in one direction, experiencing every step of that evolution as the curator intended. There’s no roaming at the Frank Lloyd Wright rotunda—the only ways are up and down.

Wright’s IKEA store of a building allows for temporality, making the curator the architect of the viewing experience more so than any other museum. Curator Katherine Brinson’s chronological placement is the most consequential aspect of “Gathering,” the Guggenheim’s building-wide retrospective of American painter Alex Katz’s career.

A native New Yorker with a thing for coastal Maine, Katz, now 95, is best known for his bold colors and flat shapes, his detached portraits and evocative landscapes. Ordered mostly chronologically, “Gathering” pulls back the curtain on the early years, featuring tiny compositions from his time at the Cooper Union, and highlights all the greatest hits, the floor-to-ceiling portraits and landscapes that prove him ahead of his time. The exhibit ends with Katz’s most recent work, products of an abstract, monochrome turn. This work from the twilight of his career prizes feeling over form, and following fifty or so of Katz’s iconic heavy hitters, ends the exhibit on a sorrowful note. But such is life. “Gathering” is a stunningly frank portrait of a lifelong artist, its relationship with time making it the deeply moving kind of exhibit that only comes around every once in a while.

It’s about time for a Katz retrospective. “Gathering” is Katz’s first major New York exhibit since a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney in 1986. His work was not considered “serious” for a long time—pop art was barely there (he was one of its forefathers), and critics tended toward abstract art. The commercialism didn’t help—Katz has been commissioned by everyone from Calvin Klein to the NYC Transit Authority for billboards and public installations. But time has proven Katz to be a great artist, far ahead of his contemporaries.

Even his work from the ‘50s, minus the dated hairstyles and clothing, looks as though it could’ve been done yesterday. The mystique of his cool, detached portraits is even more appealing today. His 2009 painting “Sharon and Vivien” graced the cover of Sally Rooney’s breakout novel “Conversations with Friends,” available at your favorite independent bookstore, and his other work endlessly proliferates on graphic designers’ Pinterest boards to this day, without attribution. Katz is an artist of the mass media age; his work reproduces well on screen. You’re bound to see plenty of Instagram photos of this exhibit, but trust that it’s way better in person.

Before the chronology truly begins, there’s a quick crash course. There is only one painting in the lobby, a kind of centerpiece, setting the stage for what’s to come (and imploring people to buy tickets.) In 2020’s “Blue Umbrella 2,” Katz depicts his wife and muse Ada in the rain, sporting a forlorn expression like a Roy Lichtenstein heroine. Katz’s masterful precision announces itself in the folds of her headscarf and the motion of the raindrops. After a lifetime of painting Ada—Katz has painted her over two hundred times since they first met in 1957—this 2020 piece is still one of the most romantic, evocative works in the exhibit. A perfect introductory piece for the Katz-curious.

A few more recent paintings, too large to be placed upstairs, set the tone for the exhibit. Yellows, blues, and “West 1,” from 1998. Pure pitch blackness, which, with a few imperfect white brushstrokes, magically becomes a uniform building at nighttime. This is one of the finest examples of Katz’s minimalistic impressionism. “West 1” is one of the only cityscapes in an exhibit full of nature scenes, which is a shame, as it is one of the show’s highlights.

The spiral of time begins with Katz’s early, small-scale work, from his student years at the Cooper Union and the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture. It’s an intimate look at his early artistic process, the years of developing his style and figuring things out. Obsessive sketches of subway scenes are ripped out of his sketchbook and framed. They culminate in 1948’s “Three Figures on a Subway,” with messy lines and colors more muted than he’s known for, but clearly setting a precedent for his iconic compositions and flat planes. “Ella Marion in a Red Sweater,” a portrait of Katz’s mother from 1946, has her shooting the viewer a wry, knowing gaze—a gaze Katz will paint to perfection over the next seventy or so years.

Katz’s love for the beach is apparent in his early work as well—he has returned to Maine every summer since his residency at Skowhegan. Beach landscapes and paper cutout experiments anticipate his understanding of form and creation of a signature palette, preceding the large-scale lithographs and screen prints further up the spiral. These small works look amateurish compared to his most iconic pieces, but all the seeds are there. There is no eureka moment, though: Katz refines his style by painting and printing and cutting and starting all over again. “Gathering” puts front and center the near-obsessive dedication required to become a great, prolific artist. It celebrates Katz’s refusal to get comfortable and his commitment to putting in the work.

It’s clearly paid off: the center of the exhibit is a highlight reel of Katz’s most iconic pieces. Lean in to scrutinize the massive portraits of his cool artist friends, and you’ll notice that some of them are composed of probably less than fifty brushstrokes. That’s all a master needs.

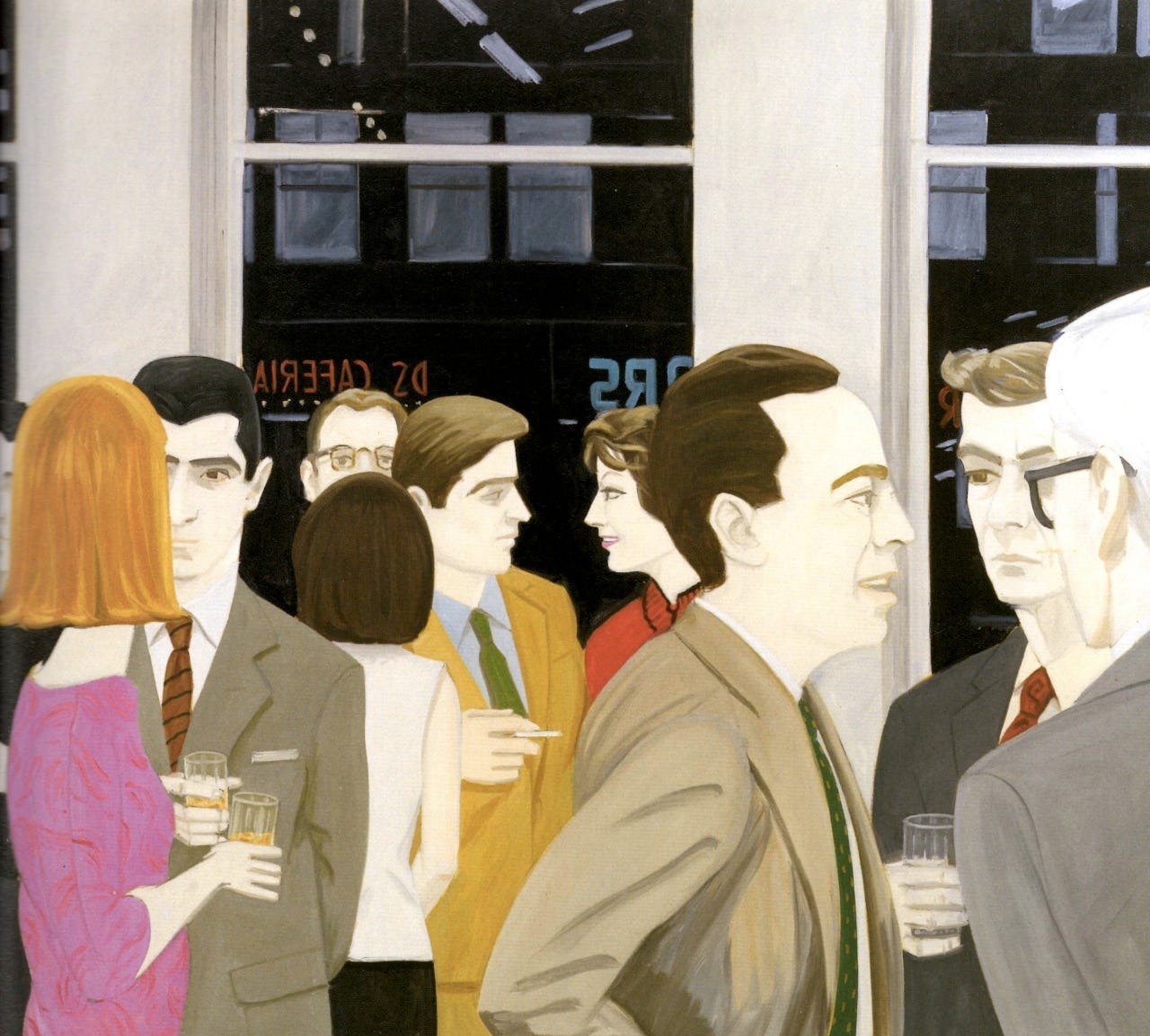

More is more sometimes, though. True to its title, “Gathering” also shines a light on Katz’s busiest paintings, the ones with groups of bodies, which aren’t necessarily his most popular. “Round Hill” and “The Cocktail Party” depict a soirée and a beach getaway that look the opposite of inviting. You can’t sit with us, they say, but you can watch. 1964’s “Paul Taylor Dance Company” is a quirky highlight that exemplifies Katz’s experiments with movement and form. Dispersed among the large canvases are Katz’s “sculptures,” which are technically wooden cutouts of paintings, inserting his work into three-dimensional spaces but never straying from his commitment to flatness.

At times, the exhibit is a who’s who of the midcentury downtown intelligentsia, featuring portraits of friends Allen Ginsberg, Frank O’Hara, and Edwin Denby. Katz has seen it all, from ‘70s fashions to ‘80s haircuts to ‘90s interiors. But if “Gathering” is a record of people and things Katz has cared about, Ada wins by miles. There is “Upside Down Ada,” “Ada Ada,” “Ada and Vincent,” “Ada in Black Sweater,” “Departure (Ada)” and “Ada” (2018), to name a few. Critics have long lampooned Katz for the seeming lack of emotion and intimacy in his work. In “Gathering,” though, reproduction (in the artistic sense) is the loudest declaration of love.

“Departure (Ada),” a hexaptych of six near-identical versions of Ada’s back, calls back to “The Black Dress,” which depicts six versions of Ada looking at the viewer. She walks into a forest-green void. That’s the last we see of her, in color.

The sea changes again, as we enter the exhibit’s third and final act. Katz’s tendency toward the natural world results in a series of immersive yet surprising landscapes. The museum supplies a quote from Katz: “There is no realistic painting, to me, that can do the whole thing; if you get the light you can’t get all the details, if you get the details you don’t get the light. Realism is a variable.” Katz’s unrealism allows him to capture sights that usually elude capturing. “Blue Night” depicts the near-pitch darkness of a starless night sky, a vague cliff in the distance, enveloping the viewer in the boundless nothingness of the beach at night. In “Lake Light,” a white mass of light sits atop a body of water, slowly blending in at the edges, translucence a subject in itself.

Katz renders landscapes with an aching universality. It’s that one night in Cape Cod last summer, or the river near grandma’s, or a puddle in front of that funny-looking building on a rainy night. You’ve been there before, you’ve just never been able to capture it.

Finally, Wright’s spiral leads you to the end destination: a small, colorless room, drenched with the specter of mortality. Here hangs Katz’s latest work—the white-brushstrokes-on-black piece “Ocean 9” was supposedly still drying as it was hung. An untitled piece is Katz’s take on the ever-divisive all-white painting, a truly confounding moment in a career that’s largely rejected emptiness. It’s a downcast note to end the exhibit on, implying he has nothing left to give.

One of the last things you see is 2021’s “Ada’s Back,” the conclusion to the exhibit’s Ada series, a close-up of the graying hairs at the back of her head. Compared to the opening piece “Blue Umbrella 2,” painted just a year prior, “Ada’s Back” feels rudimentary, like an unfinished draft. On a nearby wall, the museum offers a recent quote from Katz: “Now in some of the things I paint, I leave out the thing and just paint the sensation. The now.” Katz can still paint like he used to, it says, he just chooses not to.

The end of the exhibit is not exactly flattering for Katz, but it’s surprisingly moving. Standing in that final room, surrounded by massive canvases of near-nothingness, some will feel sadness, and some will feel peace. Some will feel inspired: Katz has done it all, and now he’s aspiring toward the impossible. If we’re lucky enough, he’ll never stop painting.

“Alex Katz: Gathering” tells the story of an artist in the making, at the height of his powers, and reaching his twilight. It is a shrine to longevity, prolificacy, and the increasingly elusive thing that is dedicating your life to art. At the end of the spiral, “Gathering” goes out with a whimper, but so will the rest of us.

Go off